GPT2 from Scratch Part 1

Published:

Part 1 - GPT2 from Scratch: Preparation of Data Pipeline

Table of Contents:

- Embeddings

- What is Embedding?

- Why is Embedding Required?

- Mathematical Definition of Embedding

- Different Types of Embeddings

- Tokenization

- What is Tokenization?

- Why is Tokenization Required?

- Implement a Simple Tokenizer

- Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) Tokenizer

- Huggingface’s 🤗 Tokenizer

- Data Pipeline for GPT

- Working Principle of GPT

- Data Sampling by Sliding Window

- Create Training Dataset

Prerequisites

Firstly, a medium level knowledge of

Python(including OOPs concepts) is required, as the implementation will be carried out in this language.A foundation level machine learning concepts is needed to understand the concepts. This includes neural networks, loss functions, training dynamics etc. The knowledge of Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) is a bonus but not strictly needed.

Experience with deep learning frameworks

PyTorchis necessary, as it will be used to build and train the model. Basic knowledge ofHuggingfacelibrary is a plus.A basic mathematical background in linear algebra and probability will support the understanding of model operations.

1. Embeddings

1.1. What is Embedding?

In the context of machine learning, an embedding is a representation of data (it could be any form of data such as audio, video, image, text etc.) in a finite-dimensional vector space. Embeddings are used to transform complex and often high-dimensional data into a more manageable, dense, and continuous vector space where similar items are closer together and dissimilar items are farther apart.

1.2. Why is Embedding Required?

The primary motivation for using embeddings is to translate high-dimensional, sparse, and non-numeric data into a lower-dimensional, dense, and numeric format that machine learning algorithms can efficiently process. This transformation facilitates better model performance.

Many machine learning models perform better when the input data is not high-dimensional due to the curse of dimensionality. Embeddings help in reducing the dimensions while retaining its essential features. Embeddings learn to capture the underlying patterns in the data, acting as learned features that are useful for various tasks like classification, clustering, or summarization.

In many real-world applications, data comes in categorical form (like words, user IDs, or item IDs) that cannot be used directly by most machine learning algorithms, which expect numerical input. Embeddings convert these categorical variables into vectors in a continuous vector space.

1.3. Mathematical Definition of Embedding

Mathematically, an embedding can be defined as a mapping: $f: X \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^d$ where:

$X$ is the original input space (possibly categorical data). $\mathbb{R}^d$ is the embedding vector space with dimension $d$. The mapping $f$ is typically a function parameterized by weights learned from the training data.

[ f: \mathbb{R}^m \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^n \quad \text{where} \quad m \gt n ]

The above equation shows one special case of using the embedding map where we are converting the embedding from $m$-dimensional vector space to $n$-dimensional vector space where $m$ is larger than $n$.

1.4. Different Types of Embeddings

Any form of data (it could be audio, image, video or text) can be converted to a point in a continuous real valued vector space known as embedding. Since the blog is more focused on NLP related applications, the embeddings related to text will be covered.

1.4.1 Word Embedding

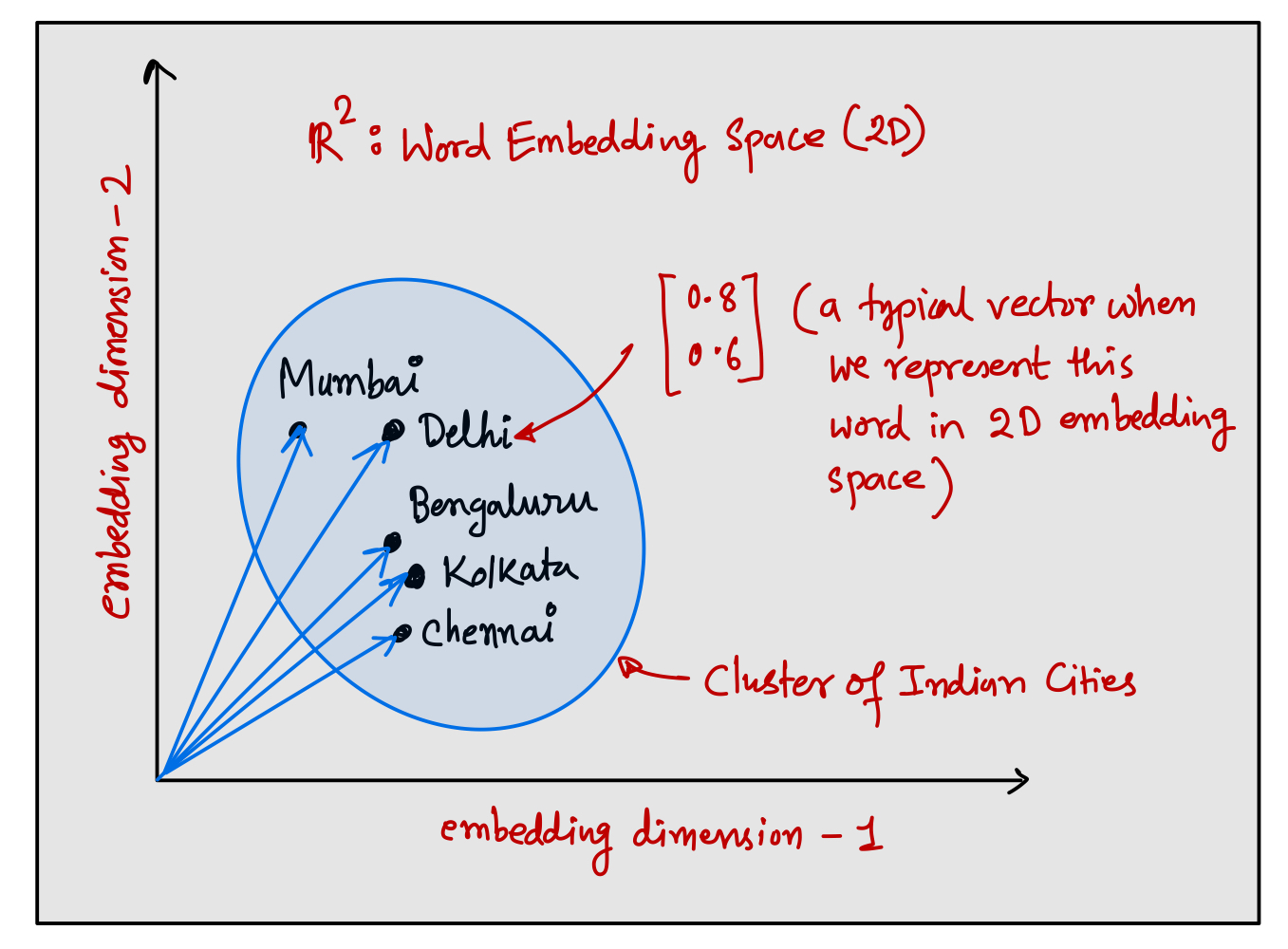

Word embeddings convert text into a set of feature vectors where each word (or more technically token) in the corpus is represented by a point in a vector space. The vectors are trained to ensure that words with similar meanings are located close to each other.

Word embeddings are extensively used in transformer based large language models (LLMs). There are several algorithms to generate word embedding but one of the most popular algorithms is Word2Vec. In principle, Word2Vec is trained using one of two architectures: CBOW (Continuous Bag of Words) or Skip-gram. In the CBOW architecture, the model predicts the current word based on the context, and in the Skip-gram architecture, it predicts surrounding context words given the current word, both using a simple neural network which is trained to optimize similarity between the word’s embedding vectors.

Inside the embedding space, words that are closely related to a particular concept would form a cluster in the embedding space. Essentially, these embeddings create a high-dimensional map where distances between points (word embedding vectors) reflect how related the words are the source language.

For language modeling task, we could use the pre-trained word embeddings such as one obtained from Word2Vec to generate the word embeddings, but it won’t be efficient due to mismatch between Word2vec’s training corpus and the GPT like LLM’s training corpus. To capture complex patterns and context in the training corpus, LLMs would generate the word embeddings on the fly, directly from the training data at the time of training the model. This embedding vector will be highly optimized for the training corpus that have been used to train the LLM.

1.4.2 Sentence/Document Embeddings

Sentence or document embeddings extend the concept of word embeddings to larger units of text, like sentences or entire documents. These embeddings capture the semantic meaning of the text in a single vector. BERT generates embeddings for sentences which can be used in natural language inference task which maps a sentence pair <A, B> to one of the label between entailment, contradiction and neutral. BERT need to know the sentence level information which is captured by sentence embedding to infer whether sentence A is an entailment (or contradiction or no relation) of sentence B.

1.4.3 Positional Embeddings

Positional embeddings are used in models that need to understand sequence order (like sentences in text or time series data), adding information about the relative or absolute position of elements in the sequence.

In NLP, models like GPT, BERT etc. use positional embeddings to retain the order of words in a sentence which is crucial for understanding context and meaning accurately. This itself is a huge topic, and it will be covered later in this blog.

2. Tokenization

2.1 What is Tokenization?

Tokenization is a fundamental process in NLP where a large body of text is divided into smaller, manageable units known as tokens. These tokens can be individual words, phrases, or even characters depending on the granularity required for the specific application.

The primary purpose of tokenization is to simplify the complex structure of natural languages into structured data that LLMs can understand and process. Each token represents a discrete piece of information, and when analyzed together, these tokens can reveal patterns and insights about the text.

In LLM, tokenization is the first step in preprocessing for many NLP tasks such as sentiment analysis, machine translation, and text generation. It allows the LLMs to efficiently perform operations on text by converting the unstructured data into a numerical format that machine learning algorithms can work with.

2.2 Why is Tokenization Required?

Natural language is inherently unstructured and variable in length. Tokenization breaks text into consistent, manageable pieces, making it easier for models to process. Tokenization allows models to handle vocabulary efficiently by representing and processing text as sequences of tokens rather than entire sentences or documents at once.

LLMs are trained on numeric data. Tokens are converted into numerical IDs called token IDs, which can be fed into embedding layer for generating the embedding vector. By breaking text into tokens, models can learn the context and meaning associated with different sequences of tokens, which is crucial for generating coherent and contextually appropriate responses.

Advanced tokenization techniques like subword tokenization (e.g., Byte-Pair Encoding) help in managing vocabulary size by breaking down rare or unknown word into known subword, allowing the model to handle a wider variety of words without significantly increasing the vocabulary size. Efficient tokenization reduces the memory footprint of the LLMs by needing fewer unique tokens for the dataset.

2.3 Implement a Simple Tokenizer

2.3.1 A Quick Refresher on re Library

In practical application, we are never going to build our own tokenizer, but it will give an idea of how the tokenization is performed in pre-built tokenizers. To build our own tokenizer, we can use Python’s regular expression re library.

import re

pattern1 = r"\s" # treats (\) as a literal (raw) char

pattern2 = r"(\s)"

text = "Hello, World. This, is a test." # treat it as training data

result1 = re.split(pattern=pattern1, string=text)

result2 = re.split(pattern=pattern2, string=text)

print(result1)

print(result2)

['Hello,', 'World.', 'This,', 'is', 'a', 'test.']

['Hello,', ' ', 'World.', ' ', 'This,', ' ', 'is', ' ', 'a', ' ', 'test.']

Note the difference between two patterns. The first pattern is not capturing the group (if the match is found based on pattern \s which means any form of whitespace) as it is not retaining the group in the final result. Since we are using capturing group (r"(...)") in the second pattern, It will capture the groups where the pattern is present while retaining the groups into the list.

The list of words in the result is called tokens. Note that there is a problem in this tokenization scheme as the list has individual words along with the punctuation. If we want to treat a word followed or preceded by punctuation, then the number of unique tokens will be large so the size of vocabulary (list of tokens) will increase exponentially. Therefore, we want to treat the punctuations as separate tokens.

In cased tokenization scheme, the case sensitivity of tokens matters for example

appleis different fromApple, so they will be treated as two different unique tokens. However, in uncased tokenization scheme, those two tokens will be treated as one unique tokenapple.

Now consider a complex tokenization pattern where we want to split the text based on all the punctuation characters, whitespace and digits but at the same time we want to retain the capturing groups as well otherwise, the groups will be lost from the list.

pattern1 = r"(--|[,.?_:;\"'()!]|\s)"

pattern2 = r"(--|[^0-9a-zA-Z])"

pattern3 = r"(--|[^0-9a-zA-Z]|\d+)"

text = "abc1-def2 -- ghi123. jkl 2 30 mno."

result1 = re.split(pattern1, text)

result2 = re.split(pattern2, text)

result3 = re.split(pattern3, text)

print(result1)

print(result2)

print(result3)

['abc1-def2', ' ', '', '--', '', ' ', 'ghi123', '.', '', ' ', 'jkl', ' ', '2', ' ', '30', ' ', 'mno', '.', '']

['abc1', '-', 'def2', ' ', '', '--', '', ' ', 'ghi123', '.', '', ' ', 'jkl', ' ', '2', ' ', '30', ' ', 'mno', '.', '']

['abc', '1', '', '-', 'def', '2', '', ' ', '', '--', '', ' ', 'ghi', '123', '', '.', '', ' ', 'jkl', ' ', '', '2', '', ' ', '', '30', '', ' ', 'mno', '.', '']

pattern1 is designed to split the text at punctuation characters (commas, periods, colons, semicolons, question marks, exclamation etc.) or whitespace characters (\s includes spaces, tabs, newlines, etc.). pattern1 splits the text on three types of occurrences which are -- (a double hyphen) or any characters from the character group or any form of whitespace. Note the special (|) symbol which means logical OR operation. The bracket ([...]) is defining a character class meaning that any characters withing the bracket will be matched for creating the groups. When it starts scanning the characters, the moment it finds pattern1 then it will pause to split the expression, captures the group and resumes scanning thereafter. Empty strings ('') appear where there are no characters between two consecutive delimiters. For example, between two consecutive delimiters ghi123. jkl (delimiters are . and \s), there is no character, so it will capture the group as empty string ('')

pattern2 splits the text on two types of occurrences. -- (a double hyphen) or [^0-9a-zA-Z] which matches any character that is not a number (0-9), not a lowercase letter (a-z), and not an uppercase letter (A-Z). Note the special (^) symbol which means logical NOT operation.

pattern3 extends pattern2 by also splitting at sequences of digits (\d+, + means one or more occurrence of a digit). The inclusion of \d+ in the pattern results in numbers being split from alphabetic characters, as well as being captured as separate tokens.

I will use

pattern1for the tokenization for simplicity. Moreover, I will not consider\sas part of vocabulary for simplicity, but they are included for real world application. To know more aboutrelibrary, you can refer to Datacamp or Programiz.

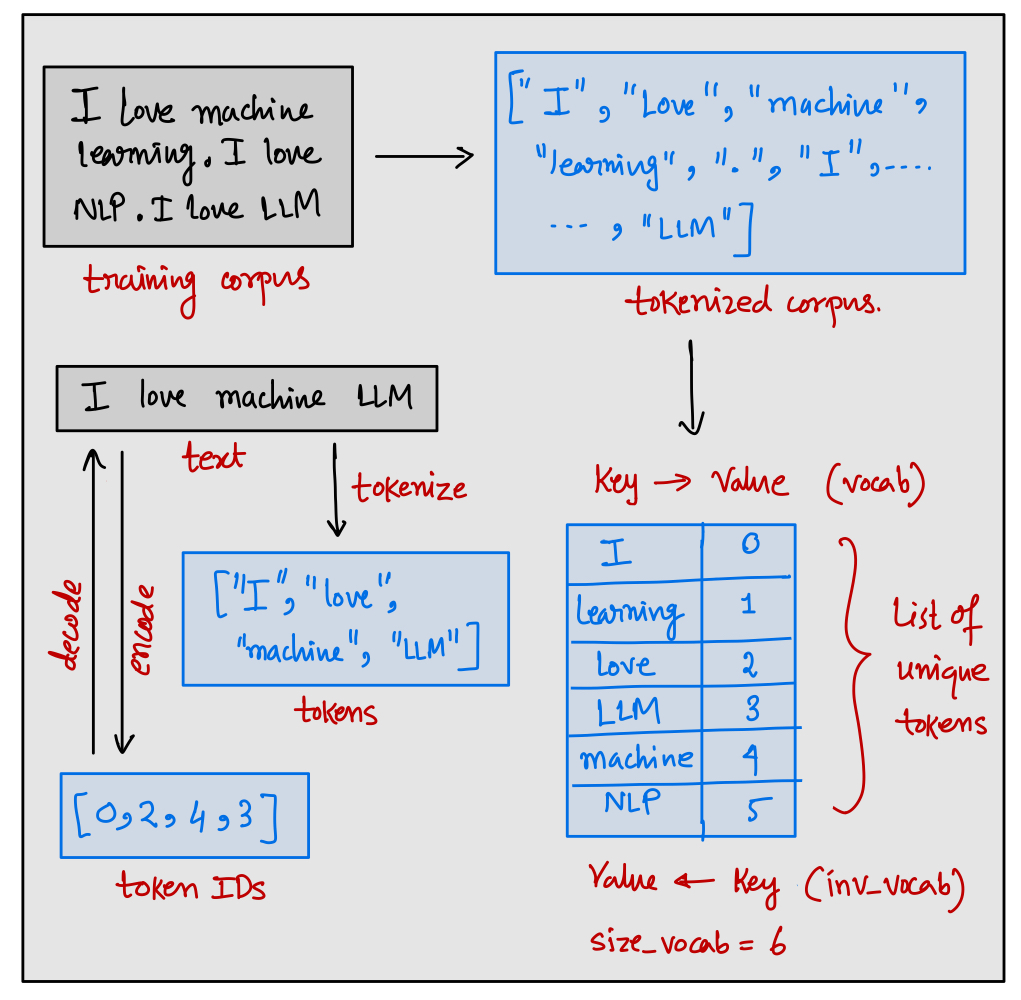

2.3.2. Convert tokens into token IDs

Once the tokens are created, we need to convert the tokens into an integer called token IDs. Given a corpus, the first task is to tokenize the entire corpus which gives us the list of tokens which is also called a vocabulary. Then the process in which we map each of the tokens of the vocabulary into an integer is called building a vocabulary. Since the vocabulary is represented as alphabetically sorted list, so the list index can be considered as token IDs. Moreover, we can also represent a vocabulary using a dictionary where the dictionary keys will be represented by tokens and the values will be represented by the corresponding token IDs. It is also possible to invert the vocabulary dictionary since it is one to one mapping between tokens and token IDs. In the inverted vocabulary, the key will represent a token ID and the value will represent its corresponding token.

The Tokenizer class should take the corpus file path as an input where we have stored the training corpus. The job of the tokenizer should be to build the vocabulary and inverse vocabulary. Therefore, the __init__ method should build the entire vocabulary and inverse vocabulary. It should also store the size of vocabulary (vocab_size), vocabulary dictionary (vocab) and inverse vocabulary dictionary (inv_vocab) as property of class. The Tokenizer class should also provide 3 basic methods which are tokenize, encode, and decode. In any prebuilt tokenizer e.g. provided by Huggingface or OpenAI, these 3 methods will be present along with other methods. The tokenize method takes a raw text as an input and outputs the list of tokens. The encode method also takes the raw text as an input and outputs the list of integer token IDs from the vocabulary. The decode method takes the list of token IDs as an input and outputs the reconstructed interpretable text from inverse vocabulary.

import re

from pathlib import Path

from typing import List

class Tokenizer:

def __init__(self, corpus_file_path: Path) -> None:

self.vocab_size = None

self.vocab = None

self.inv_vocab = None

pass

def tokenize(self, text: str) -> List[str]:

pass

def encode(self, text: str) -> List[str]:

pass

def decode(self, token_ids: List[int]) -> str:

pass

So far, I have just defined the prototype of the class Tokenizer. Before, I start implementing the interface of the class, I have to talk about the importance of special tokens.

2.3.3. Special Tokens

There is a problem in the vocabulary shown in the figure. What if I call the encode method on some sample text where some tokens are not part of vocabulary?

tokenizer = Tokenizer("corpus.txt")

text = "Do you love LLM?"

token_ids = tokenizer.encode(text) # Raises KeyError

Note that the tokens Do, you, ? are not part of the vocabulary so if we try to access the key (or token) from the dictionary vocab then it will raise KeyError. The solution will be to add a special token <unk> to represent unknown tokens that were not part of the training corpus, thus not part of the existing vocabulary. Therefore, if the tokenizer encounters a word that is not part of the vocabulary, then it is going to replace the unknown tokens by <unk>.

There are other special tokens as follows:

<bos>or[CLS]or</s>: This token is called beginning of sequence token, and it is used to mark the start of the token sequence. It helps the LLM to understand where a piece of content begins.<eos>or[SEP]: This token is called end of sequence token, and it is positioned at the end of the sequence. It is useful when we want to concatenate multiple unrelated texts in a sequence.<pad> or [PAD] or [MASK]: This token is called padding token. The inputs to any LLM is processed in batches. In a batch of sequences, the batch may have varying length of texts. To ensure that all text have same length, the shorter length texts are extended using the padding token.

The usage of special tokens is architecture and task dependent. The name of the special tokens are immaterial. It all depends on the context where we want to use the special token. For example, you can use [MASK] for padding as well as masking some words intentionally in the sequence. Note that GPT2 model does not use any of the above tokens. Rather, it uses <|endoftext|> for <bos> and <eos>. For padding also, it uses the same <|endoftext|> token because, in the attention mechanism, we generally do not attend the padding tokens, so the choice of padding token is immaterial. GPT2 doesn’t require an <unk> token either for a reason that will be clarified later in the BPE section.

When we train an LLM on multiple unrelated documents (it could be books, news articles, Wikipedia pages, internet crawl etc.), it is common to shift the context from one document to another document. We need a way to tell the LLM that the context of two documents are different, and they are unrelated. Therefore, we insert a context token

<|endoftext|>before starting of each document which helps the LLM to understand that the text sources are being concatenated for training, although they are contextually unrelated from each others.

text1 = "<|endoftext|> This is a text on Machine Learning"

text2 = "<|endoftext|> This is a text on Russia-Ukraine war"

text3 = "<|endoftext|> This is a text on Indian Mythology"

text4 = "<|endoftext|> This is a text on US democracy"

text = text1 + text2 + text3 + text4 # defines a sequence for LLM training

Note that a token sequence can consist of multiple unrelated tokens as long as it doesn’t exceed the maximum supported sequence length of the LLM. Every LLM can support some finite number of tokens in one sequence (for GPT2, it is 1024 tokens). Since, this number is quite large, it is very common to include multiple contextually different texts in same sequence but separated by <|endoftext|> token.

2.3.4 Code of Simple Tokenizer

class Tokenizer:

def __init__(self, corpus_file_path: Path) -> None:

self.pattern = r"(--|[,.?_:;\"'()!]|\s)"

with open(corpus_file_path, "r") as f:

raw_text = f.read()

tokens = self.tokenize(raw_text)

unique_tokens = sorted(list(set(tokens)))

unique_tokens.extend(["<|endoftext|>"])

self.vocab = {j:i for i,j in enumerate(unique_tokens)}

self.inv_vocab = {j:i for i,j in self.vocab.items()}

self.vocab_size = len(self.vocab)

def tokenize(self, text: str) -> List[str]:

tokens = re.split(self.pattern, text)

tokens = [i.strip() for i in tokens if i.strip()]

return tokens

def encode(self, text: str) -> List[str]:

tokens = self.tokenize(text)

token_ids = []

for token in tokens:

if token in self.vocab.keys():

token_id = self.vocab[token]

else:

token_id = self.vocab["<|endoftext|>"]

token_ids.append(token_id)

return token_ids

def decode(self, token_ids: List[int]) -> str:

tokens = [self.inv_vocab[i] for i in token_ids]

text = " ".join(tokens)

return text

First, I am tokenizing the entire corpus using the tokenize method where the corpus is split into token streams and then filtering out the empty and whitespace tokens. Furthermore, I am also adding the special context <|endoftext|> token to handle unknown words and other context.

To test the Tokenizer, I will download a book (Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare) in .txt format from Gutenberg. You can download any other books of your choice from the Gutenberg project page.

import random

random.seed(42) # For reproducing the results

current_dir = Path.cwd()

tokenizer = Tokenizer(Path(current_dir, "tokenizer/corpus/pg1513.txt"))

print(f"Size of vocabulary: {tokenizer.vocab_size}")

print("Random 10 tokens from vocabulary: ",

random.sample(list(zip(tokenizer.vocab.items())), k=10))

print("<|endoftext|> token id: ", tokenizer.vocab["<|endoftext|>"])

Size of vocabulary: 4934

Random 10 tokens from vocabulary: [(('Veronese', 912),), (('Contents', 204),), (('fisher', 2253),), (('drunk', 2006),), (('delay', 1828),), (('apply', 1143),), (('They', 839),), (('true', 4467),), (('Rosaline', 712),), (('year', 4837),)]

<|endoftext|> token id: 4933

When I give the path of the book pg1513.txt, then the tokenizer creates the vocabulary from the contents of that book. It creates overall 4934 tokens from the corpus and some tokens and its corresponding token IDs can be seen in the output. As expected, the <|endoftext|> token gets the last entry in the vocabulary as a special token.

orig_text = "I love machine learning. Do you also love ML?"

token_ids = tokenizer.encode(text=orig_text)

dec_text = tokenizer.decode(token_ids=token_ids)

print(orig_text)

print(token_ids)

print(dec_text)

I love machine learning. Do you also love ML?

[423, 2944, 4933, 2832, 10, 249, 4848, 1097, 2944, 4933, 39]

I love <|endoftext|> learning . Do you also love <|endoftext|> ?

Note that, the training corpus is related to Romeo and Juliet, so it is expected that the token machine will not be present in the corpus. Therefore, the tokenizer maps the token machine into the unknown token <|endoftext|>. Careful readers will notice one difference between the original text and the decoded text. You can fix this difference, if you use the following decoder method.

def decode(self, token_ids: List[int]) -> str:

tokens = [self.inv_vocab[i] for i in token_ids]

text = " ".join(tokens)

text = re.sub(r"\s+(--|-|[_\(\)':;,.?!])", r"\1", text) # Added to fix whitespace

text = re.sub(r"(--|-|[_\(\)'])\s+", r"\1", text) # Added to fix whitespace

return text

When run on the updated decoder method, it will produce the following output:

I love machine learning. Do you also love ML?

[423, 2944, 4933, 2832, 10, 249, 4848, 1097, 2944, 4933, 39]

I love <|endoftext|> learning. Do you also love <|endoftext|>?

The re.sub function replaces the found pattern (in the argument) with just the punctuation mark (\1 refers to the first captured group, which is the punctuation mark itself). This prevents spaces from appearing before these punctuation marks, which is a common formatting rule in English text (e.g., there should be no space before a period or a comma). The second pattern captures a set of punctuation marks that might be incorrectly spaced after (--, -, _, (, ), '). It looks for these punctuation marks followed by one or more whitespace characters and replaces the entire sequence with just the punctuation mark (\1). This ensures that certain punctuation marks are not followed by an unintended space.

2.4. Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) Tokenizer

2.4.1 What is Subword Tokenization?

We have already seen that splitting a text into smaller chunks gives tokenized text. There are many ways to perform the tokenization process. A naive way could be to split the text by whitespace. As we have seen earlier that in this method, the punctuation characters would be attached to the tokenized words. Therefore, we should take the punctuation characters as separate tokens. However, if we use punctuation and spaces for tokenization then some English words will completely lose its meaning. For example, shouldn't, could't, wouldn't etc. will be tokenized as shouldn, ', t which doesn’t make sense. It would have been better, had we tokenized it as should and n't. This was an example of rule-based tokenization where depending on rules, we tokenize a text (Spacy library employs it).

Space-based, Punctuation-based and Rule-based are all examples of word tokenization which means splitting the sentence into words. One downside of word tokenization method is that the size of the vocabulary will be large. As a result, the embedding matrix that the GPT model learns will be enormous and unmanageable (size of embedding matrix is vocab_size by embedding_dimension). Another option could be character level tokenization which treats each individual character as a token. This tokenization is least preferred because it makes the model harder to learn any meaningful representation from the tokens due to its atomic nature.

Subword tokenization is a method used to break down words into smaller, meaningful units called subwords. This approach bridges the gap between character-level and word-level tokenization. The fundamental principle behind subword tokenization is to decompose words into frequently occurring substrings, ensuring that even if a word has never been encountered before, its components can be recognized and processed.

In short, frequently used words should not be split into smaller subwords but rarely used words should be decomposed into meaningful subwords so that the size of vocabulary can be reduced. There are two popular subword tokenization methods used in LLMs: Byte Pair Encoding (BPE), which is used in GPT models, and WordPiece, which is used in BERT models.

2.4.2 What is BPE?

Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) is a technique originally developed for compressing text data but has since been adapted for use in NLP as a subword tokenization method. The process involves starting with a basic vocabulary of individual characters and iteratively merging the most frequently occurring pairs of adjacent characters to form new, composite tokens.

The iterative merging process in BPE continues until the vocabulary reaches a pre-defined size or a set number of merges has been executed. Since BPE breaks down words into known subwords, a model trained with BPE can process and generate words that were not explicitly seen during training, effectively dealing with rare words or unknown words. Additionally, BPE reduces the overall vocabulary size necessary for model training, which in turn reduces the model’s memory footprint.

2.4.3 BPE Algorithm

Consider the following corpus for simplicity:

hello, world!

hello world.

First, the entire corpus is tokenized into individual words using a pre-tokenization scheme such as whitespace-based tokenizer or punctuation-based tokenizer. I am going to use punctuation-based pre-tokenizer that ignores the whitespace characters. At the end of each word, a special end-of-word symbol (like <|endoftext|> or </w> or similar) is added to mark the end of each word which handles the word boundary. For simplicity, let’s use </w> as the end-of-word marker:

['hello', ',', 'world', '!', 'hello', 'world', '.']

['hello</w>', ',</w>', 'world</w>', '!</w>', 'hello</w>', 'world</w>', '.</w>']

BPE starts with a basic initial vocabulary of individual characters that appear in the corpus text along with the special end-of-word symbol.

Vocabulary: {'h', 'e', 'l', 'o', ',', 'w', 'r', 'd', '!', '.', '</w>'}

Now represent the pre-tokenized words followed by </w> as sequence of tokens from initial vocabulary. Collect the adjacent pair of symbols in all the words by a sliding window of 2 symbols.

h e l l o </w> : (h, e), (e, l) , ..., (o, </w>)

, </w> : (,, </w>)

w o r l d </w> : (w, o), (o, r), ..., (d, </w>)

! </w> : (!, </w>)

h e l l o </w> : (h, e), (e, l), ..., (o, </w>)

w o r l d </w> : (w, o), (o, r), ..., (d, </w>)

. </w> : (., </w>)

Now we can count the frequency of these pair of symbols as the number of times these pairs occur in the pre-tokenized word stream. Identify the most frequent pair of symbols (often called byte pair) and merge it to represent as a single symbol. For example, (h, e) is the most frequent byte pair, so we merge it to form a new symbol he.

(h, e): 2 (most frequent byte pair so merged to "he")

(e, l): 2 (most frequent byte pair so merged to "el")

(l, l): 2 (most frequent byte pair so merged to "ll")

(l, o): 2 (most frequent byte pair so merged to "lo")

(o, </w>): 2 (most frequent byte pair so merged to "o</w>")

(w, o): 2 (most frequent byte pair so merged to "wo")

(o, r): 2 (most frequent byte pair so merged to "or")

(r, l): 2 (most frequent byte pair so merged to "rl")

(l, d): 2 (most frequent byte pair so merged to "ld")

(d, </w>): 2 (most frequent byte pair so merged to "d</w>")

(,, </w>): 1 (less frequent byte pair so not merged)

(., </w>): 1 (less frequent byte pair so not merged)

(!, </w>): 1 (less frequent byte pair so not merged)

After merging the symbols, we will update the vocabulary by extending the previous vocabulary as those symbols might still appear later in the text and repeat the same process until we reach a desired vocabulary size. From next iteration onwards, we should tokenize the text by looking for the longest matches in the vocabulary.

Vocabulary: {'h', 'e', 'l', 'o', ',', 'w', 'r', 'd', '!', '.', '</w>', 'he', 'll', 'o</w>', 'wo', 'rl', 'd</w>'}

he ll o</w> : (he, ll), (ll, o</w>)

, </w> : (,, </w>)

wo rl d</w> : (wo, rl), (rl, d</w>)

! </w> : (!, </w>)

he ll o</w> : (he, ll), (ll, o</w>)

wo rl d</w> : (wo, rl), (rl, d</w>)

. </w> : (., </w>)

(he, ll): 2 (most frequent byte pair so merged to "hell")

(ll, o</w>): 2 (most frequent byte pair so merged to "llo</w>")

(wo, rl): 2 (most frequent byte pair so merged to "worl")

(rl, d</w>): 2 (most frequent byte pair so merged to "rld</w>")

(,, </w>): 1 (less frequent byte pair so not merged)

(., </w>): 1 (less frequent byte pair so not merged)

(!, </w>): 1 (less frequent byte pair so not merged)

Final Vocabulary: {'h', 'e', 'l', 'o', ',', 'w', 'r', 'd', '!', '.', '</w>', 'he', 'll', 'o</w>', 'wo', 'rl', 'd</w>', 'hell', 'llo', 'worl', 'rld</w>'}

Suppose the target vocabulary size was set to 20. Since we have reached a vocabulary of size 21, we can stop the BPE algorithm here. The final vocabulary includes the initial symbols and the merged symbols (known as subwords).

Initially one might think that BPE is creating large number of vocabulary even for a small corpus text. However, this is not true because, in a large corpus, even though the number of initial pre-tokens (individual characters or basic units) can be extremely high (in billions), the BPE algorithm systematically reduces complexity (~50,000) by merging the most frequent pairs.

When BPE tokenizer encounters a word that isn’t in its predefined vocabulary, it doesn’t just give up or replace the word with a generic unknown symbol such as

<unk>. Instead, it cleverly breaks the word down into smaller pieces, known as subwords, which are already in its vocabulary. These subwords are the building blocks it uses to construct any word. So, even if the complete word is new to the model, the pieces of the word are not. By assembling these familiar subwords in new ways, the BPE tokenizer can represent virtually any word it comes across, enabling it to handle new or unusual words easily. This feature makes BPE a tokenizer that doesn’t require a special unknown token<unk>to manage words not seen in the training data. That is the reason why GPT2 tokenizer which uses BPE tokenization scheme doesn’t need an<unk>token to handle unknown words.

Unknown Word: "Anthropomorphize"

Tokens: ["An", "thro", "po", "mor", "ph", "ize"]

Token IDs: [289, 1034, 345, 786, 245, 876]

2.4.4 GPT2 Tokenizer: tiktoken

Implementing BPE from scratch is beyond the scope of this blog. Therefore, I will use OpenAI’s tiktoken library which implements BPE algorithm. From tiktoken library, we can see the entire vocabulary that was created out of GPT2’s training corpus. Moreover, it provides methods for encoding the text and decoding the sequence of token IDs.

GPT2’s tokenizer starts from an initial vocabulary of 256 ASCII characters. Then it updates the vocabulary after merging the symbol pairs until a desired vocabulary size of 50,256 is achieved. That means, during the merging process, it adds 50,000 new tokens. Moreover, it has a special token <|endoftext|> which makes the size of the vocabulary as 50,257.

import tiktoken, random

random.seed(42)

tokenizer = tiktoken.get_encoding("gpt2") # similar to tokenizer = Tokenizer(...)

print(f"Size of vocabulary: {tokenizer.n_vocab}")

print("Random 10 tokens from vocabulary: ",

random.sample(list(zip(tokenizer._mergeable_ranks.items())), k=10))

print("Special tokens: ", tokenizer._special_tokens)

print("<|endoftext|> token ID: ", tokenizer.eot_token) # index starts from 0!

Size of vocabulary: 50257

Random 10 tokens from vocabulary: [((b' divest', 41905),), ((b' anx', 7296),), ((b'You', 1639),), ((b' coasts', 48598),), ((b' Oz', 18024),), ((b' Vi', 16049),), ((b' Happy', 14628),), ((b' appreciate', 9144),), ((b' tcp', 48265),), ((b' guilty', 6717),)]

Special tokens: {'<|endoftext|>': 50256}

<|endoftext|> token ID: 50256

Similar to our own Tokenizer class, tiktoken also provides two most important methods: encode and decode.

text = "Hello there! How are you doing today? <|endoftext|> Do you like movies?"

en1 = tokenizer.encode(text, disallowed_special=(tokenizer.special_tokens_set - {'<|endoftext|>'}))

de1 = tokenizer.decode(en1)

en2 = tokenizer.encode(text, allowed_special={'<|endoftext|>'})

de2 = tokenizer.decode(en2)

print(text)

print([tokenizer.decode([i]) for i in en1])

print(de1)

print([tokenizer.decode([i]) for i in en2])

print(de2)

Hello there! How are you doing today? <|endoftext|> Do you like movies?

['Hello', ' there', '!', ' How', ' are', ' you', ' doing', ' today', '?', ' <', '|', 'end', 'of', 'text', '|', '>', ' Do', ' you', ' like', ' movies', '?']

Hello there! How are you doing today? <|endoftext|> Do you like movies?

['Hello', ' there', '!', ' How', ' are', ' you', ' doing', ' today', '?', ' ', '<|endoftext|>', ' Do', ' you', ' like', ' movies', '?']

Hello there! How are you doing today? <|endoftext|> Do you like movies?

Note that I am using an argument allowed_special which enforces the tokenizer to treat the string literal <|endoftext|> as a special token and not the string literal. Without this argument, it will treat <|endoftext|> as string literal, and it will tokenize this literal as usual (but you have to remove it from disallowed_special set). You can see the output en2 (in list of tokens instead of token IDs), has not broken down the word <|endoftext|> into tokens unlike the output en1.

2.4.5 Wordpiece Tokenizer

We have already seen one popular subword-based tokenizer: BPE tokenizer which is used in GPT model. There is another type of subword-based tokenizer: Wordpiece tokenizer which is used in BERT model. Wordpiece is similar to BPE, but it doesn’t choose the most frequent byte pair (that was the case in BPE). BPE rather chooses the byte pair that maximizes the likelihood of the training data once that token is added in the vocabulary. A typical Wordpiece tokens would look like:

Word: "Anthropomorphize"

Tokens: ['An', '##throp', '##omo', '##rp', '##hi', '##ze']

The Wordpiece tokenizer would split the words into multiple tokens where ## means the rest of the tokens should be attached to the previous token without space. The details of Wordpiece tokenizer is out of the scope of this blog.

2.5 Huggingface’s 🤗 Tokenizer

I have already implemented a word-level simple Tokenizer from scratch. However, for real world application, nobody will develop a BPE or Wordpiece tokenizer from scratch! Therefore, we should rely on an external library such as Huggingface where we can take the implementation of the tokenizer such as BPE or Wordpiece.

Note that I am talking about the implementation of the tokenizer. That means, Huggingface’s

tokenizerslibrary contains all the classes related to BPE or Wordpiece tokenizer so that we don’t have to code them from scratch. After choosing one of the tokenizer class, we have to train the tokenizer on our corpus so that we build the vocabulary out of our own selected corpus. This is fundamentally different from taking a pre-trained tokenizer which was trained on somebody else’s corpus. For example, Huggingface’stransformerslibrary provides all the pre-trained tokenizers such asBertTokenizerorGPT2Tokenizeretc. These pre-trained tokenizers were trained on an enormous corpus which we don’t have access, but we have the access to the vocabulary that was created out of that corpus. Therefore, these pre-trained tokenizers would be used most of the time unless we want to pre-train an LLM on our own customized corpus. In that case, for that customized corpus, we have to build the vocabulary using the tokenizer classes provided by thetokenizerslibrary. As a rule of thumb, if you want to use other’s vocabulary then usetransformerslibrary, otherwise usetokenizerslibrary to build your own vocabulary.

The main class that handles the tokenization process is class tn.Tokenizer which takes the model as an input and returns the tokenizer object.

import tokenizers as tn

model = tn.models.BPE() # A BPE model

tokenizer = tn.Tokenizer(model) # A BPE tokenizer class

Once we get the appropriate tokenizer, next we need to set the trainer so that it can be trained to build the vocabulary out of our own corpus. In the trainer class such as tn.trainers.BpeTrainer, we need to provide the desired vocabulary size, special tokens etc. so that it can make use of those during the training. As we have already seen that, a BPE tokenizer needs a pre-tokenization scheme. For pre-tokenizer, we can use the Split or Whitespace or Punctuation class which will tokenize the text based on either a pattern or whitespace or punctuations.

To train the tokenizer, we will use tokenizer.train method whose inputs will be the list of corpus files path and the trainer object which stores the configurations for the training (returned by tn.trainers.BpeTrainer). I will train this BPE tokenizer on the same corpus (Romeo and Juliet book) that I used to train my own simple Tokenizer.

tokenizer.decoder = tn.decoders.BPEDecoder()

tokenizer.pre_tokenizer = tn.pre_tokenizers.Split(pattern=r"\s", behavior="merged_with_next")

trainer = tn.trainers.BpeTrainer(vocab_size=1000,

show_progress=True,

special_tokens=["<|endoftext|>"])

tokenizer.train(files=["tokenizer/corpus/pg1513.txt"],

trainer=trainer)

print(f"Size of vocabulary: {tokenizer.get_vocab_size()}")

print(f"Random 10 tokens from vocabulary: ",

random.sample(list(zip(tokenizer.get_vocab().items())), k=10))

print(f"<|endoftext|> token id: ", tokenizer.token_to_id("<|endoftext|>"))

[00:00:00] Pre-processing files (0 Mo) ██████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████ 100%

[00:00:00] Tokenize words ██████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████ 3557 / 3557

[00:00:00] Count pairs ██████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████ 3557 / 3557

[00:00:01] Compute merges ██████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████ 907 / 907

Size of vocabulary: 1000

Random 10 tokens from vocabulary: [(('from', 300),), (('To ', 333),), (('._]', 255),), (('REN', 433),), (('s ', 97),), (('end ', 646),), (('Project Gutenberg', 375),), (('ey ', 933),), (('Wi', 698),), (('an ', 256),)]

<|endoftext|> token id: 0

Note that I am using Split pre-tokenizer instead of Whitespace tokenizer because the Whitespace tokenizer would remove the whitespace from the tokens therefore, the decoded text will not have the whitespace (the decoded text would look like IloveML.DoyoualsoloveML - awful without the spaces!). If you want to remove the whitespace from tokens, consider using Whitespace pre-tokenizer.

You can save and load the tokenizer once it has been trained so that you don’t have to train the tokenizer again.

tokenizer.save(path) # saves the tokenizer vocabulary in path

tokenizer = tn.Tokenizer.from_file(path) # loads the saved tokenizer from path

Once, the tokenizer is trained, let’s test it to encode and decode texts. Note that I am replacing the naive decode method of tokenizer which joins the tokens by whitespace during decoding with BPEDecoder that will take care of the spaces of during decoding.

text = "I love machine learning. <|endoftext|> Do you also love ML?"

encoded = tokenizer.encode(text)

decoded = tokenizer.decode(encoded.ids, skip_special_tokens=False)

print(text)

print(encoded.tokens)

print(encoded.ids)

print(decoded)

I love machine learning. <|endoftext|> Do you also love ML?

['I ', 'love ', 'ma', 'ch', 'ine ', 'le', 'ar', 'n', 'ing', '. ', '<|endoftext|>', ' ', 'Do ', 'you', ' a', 'l', 'so ', 'love ', 'M', 'L', '?']

[138, 403, 198, 127, 507, 150, 109, 71, 124, 132, 0, 3, 971, 128, 125, 69, 415, 403, 41, 40, 28]

I love machine learning. <|endoftext|> Do you also love ML?

Without the BPEDecoder, the decoded text will look something like:

I love ma ch ine le ar n ing . <|endoftext|> Do you a l so love M L ?

Without the Split, the decoded text output will look something like:

Ilovemachinelearning.<|endoftext|>DoyoualsoloveML?

3. Data Pipeline for GPT

3.1. Working Principle of GPT

3.1.1 Goal of GPT like LLM

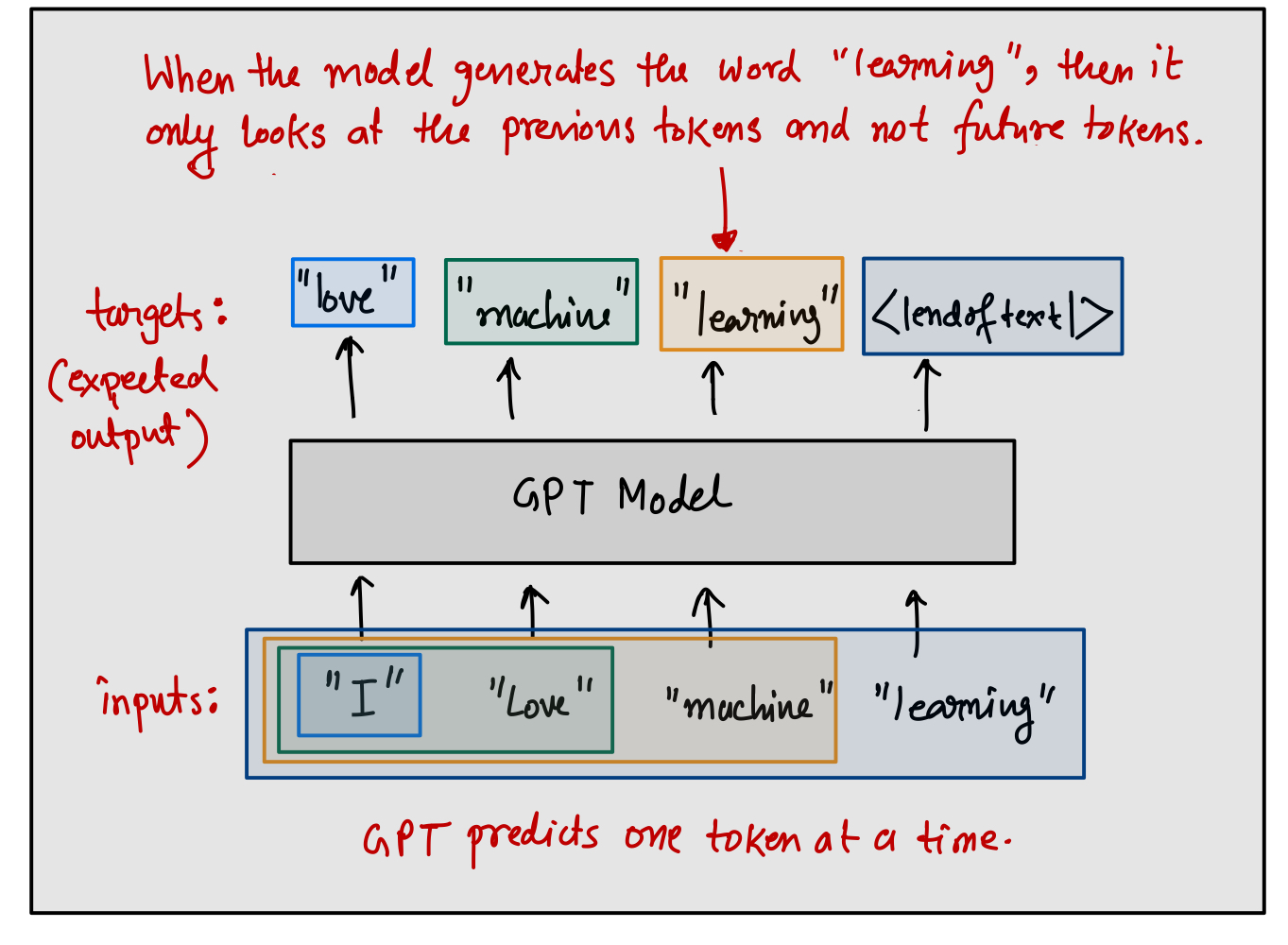

In the architecture of GPT, the task of generating text is approached as a sequence generation problem where the model predicts one token at a time. Each token generated is conditioned on the tokens that precede it, and outputs the probability distribution of the generated token conditioned on previous tokens which is learned during the model’s training phase. This approach is what allows GPT models to create coherent, and contextually appropriate text based on the input provided.

Mathematically, from the GPT, we try to predict the token $\mathbf{t}^{(i)}$ given the previous sequence of tokens $(\mathbf{t}^{(j)})_{j = 1}^{j = i-1}$. Suppose the GPT predicts the token $\mathbf{t}^{(i)}$ with probability:

[ \mathbb{P}(\mathbf{t}^{(i)} \mid \mathbf{t}^{(i-1)}, \dots, \mathbf{t}^{(1)}) ]

During the training phase, we try to learn this probability distribution by minimizing the cross entropy loss between the true token and the predicted token which is generated by the GPT model. When given a prompt or a starting sequence of tokens (also called context), the GPT model generates the next token that is most likely to follow from the given context. This is achieved through a softmax layer that outputs a probability distribution over the entire vocabulary, and the token with the highest probability is selected as the next token in the sequence.

In short, the GPT model predicts the next token based on the information of previous tokens. This is called autoregressive nature of the model which means, when the model generates a token $\mathbf{t}^{(i)}$, then it should not look at the future tokens’ information such as $(\mathbf{t}^{(i+1)}, \mathbf{t}^{(i+2)},\dots,\mathbf{t}^{(T_{max})})$. Rather, it should only look at the previous tokens such as $(\mathbf{t}^{(i-1)}, \mathbf{t}^{(i-2)},\dots,\mathbf{t}^{(1)})$. This is crucial to understand because, we are not providing the input that is limited to only the previous tokens, rather we are providing the entire token sequence that the model supports (up to model’s maximum context length ($T_{max}$), a concept which will be discussed in next section).

Note that the GPT model outputs the context vector $\mathbf{z}$ at every token position. To generate the predicted token at a token position $i$, we will feed the context vector $\mathbf{z}^{(i)}$ to a softmax layer over the length of vocabulary. The index corresponding to the maximum softmax probability will denote the predicted token. This figure shows that if we provide a sequence, then it has the capability of generating tokens at all the token positions since the models outputs context vector at all token position.

During training, we would be interested to predict the tokens at all positions but during inference, we would be interested to predict the token at the last position. This is because, we want to minimize the loss at all the token positions, therefore, we would want to predict the tokens at all the token positions. However, note that the predicted token will not always match with the true target token shown in the figure. If there is a mismatch between the true target token and the predicted token, then the model will incur some loss which will be backpropagated through the layers of the GPT model and that is how the model “learns” to predict accurate tokens at all the token position.

During inference, GPT predicts one token at a time at the last token position as shown in the Figure. The predicted token will then be appended with the input tokens and fed into the model again to predict another token. This process will continue until <|endoftext|> token is predicted or a maximum number of generated tokens is reached. However, you must understand the fact that once the model sees an input sequence, it processes the entire sequence at one step to generate the new token. Therefore, the model will predict a new token at one time step.

3.1.2 Difference between RNN and GPT

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and GPT like architectures represent fundamentally different approaches to handling sequence data in neural networks. RNNs process sequences in a step-by-step manner, maintaining a hidden representation that updates with each item in the sequence. However, this sequential dependency leads to difficulties in parallelizing the process, which can make training on longer sequences computationally expensive and slow. To train the RNN, we have to process one token at a time. That means without processing the current token, we won’t be able to move to the next token.

Text: "I love machine learning."

Tokens: ["I", "love", "machine", "learning", "."]

Token IDs: [T1, T2, T3, T4, T5]

Hidden states: [h1, h2, h3, h4, h5]

Output states: [z1, z2, z3, z4, z5]

at time step 1: z1, h1 = RNN(T1, h0)

at time step 2: z2, h2 = RNN(T2, h0, h1)

at time step 3: z3, h3 = RNN(T3, h0, h1, h2)

at time step 4: z4, h4 = RNN(T4, h0, h1, h2, h3)

at time step 5: z5, h5 = RNN(T5, h0, h1, h2, h3, h4)

If we pass this sequence of tokens to the RNN, then it will process T1 first which generates the hidden state h1 and output z1. Then in second step, it will make use of h1 and T2 which generates the hidden state h2 and output z2 and so on. Therefore, you can see that the computation in RNN is sequential in nature. To get the output states, we must process the sequence sequentially which makes the time complexity of RNN computation as $O(T \times r)$ if we assume each RNN cell takes $r$ units of time and there are total $T$ tokens.

GPT, on the other hand, eliminates the need for sequential processing of data by using an attention mechanism that learns the importance of each part of the input data relative to other parts. This architecture allows each position in the sequence to be processed simultaneously, enhancing the parallelization.

Text: "I love machine learning."

Tokens: ["I", "love", "machine", "learning", "."]

Token IDs: [T1, T2, T3, T4, T5]

Output states: [z1, z2, z3, z4, z5]

at time step 1: [z1, ..., z5] = GPT([T1, ..., T5])

Using attention mechanism, the output states corresponding to each token can be generated at one time step by processing the tokens in parallel. This is why the GPT architecture is faster than RNN as the computation is performed in a single time step. The attention mechanism will be discussed in detail in Part 2 of this blog.

3.1.3 Context Length

You might think that since the GPT model can process all the tokens at one time step, so we can increase the number of input tokens $T$ indefinitely. Unfortunately, this is not true. Parallelization in computation does not mean that the computational complexity of GPT is completely independent of $T$. Of course, it will be less that its RNN counterpart but increasing $T$, also increases computational overhead (actually quadratically!) within GPT which will be more clear in Part 2 of this blog. Therefore, we need to restrict the number of tokens that the model can support at one step of computation.

Context length refers to the maximum number of tokens from the input that the model can consider at one time while processing text. Context length determines how many tokens from the past a model can look back on when making predictions about the next token in a sequence. For instance, if a GPT model has a context length of 512 tokens, it means the model can consider and utilize up to 512 tokens of prior text to inform its generation of subsequent text.

A longer context length allows the model to “remember” more of the previous text, thereby improving its ability to understand context over longer stretches of text. However, increasing context length requires more memory and computational power, as the model needs to manage larger amounts of information simultaneously. In summary, every GPT model supports a limited context length which defines its capability. If the input sequence has more number of tokens than its maximum supported context length, then either we can discard that input from training or we can truncate the sequence up to its maximum supported context length.

3.2. Data Sampling by Sliding Window

Suppose, a training corpus text looks like:

"Generative pre-trained transformers (GPT) are a type of large language model (LLM) and a prominent framework for generative artificial intelligence.

They are artificial neural networks that are used in natural language processing tasks.

GPTs are based on the transformer architecture, pre-trained on large data sets of unlabelled text, and able to generate novel human-like content.

As of 2023, most LLMs have these characteristics and are sometimes referred to broadly as GPTs."

The first step will be to tokenize the training corpus so that we get a stream of tokens. For simplicity, I am splitting the text based on whitespace only but in reality BPE will be used for tokenization.

['Generative', 'pre-trained', 'transformers', '(GPT)', 'are', 'a', 'type', 'of', 'large', 'language', 'model', '(LLM)', 'and', 'a', 'prominent', 'framework', 'for', 'generative', 'artificial', 'intelligence.',

'They', 'are', 'artificial', 'neural', 'networks', 'that', 'are', 'used', 'in', 'natural', 'language', 'processing', 'tasks',

'GPTs', 'are', 'based', 'on', 'the', 'transformer', 'architecture,', 'pre-trained', 'on', 'large', 'data', 'sets', 'of', 'unlabelled', 'text,', 'and', 'able', 'to', 'generate', 'novel', 'human-like', 'content.',

'As', 'of', '2023,', 'most', 'LLMs', 'have', 'these', 'characteristics', 'and', 'are', 'sometimes', 'referred', 'to', 'broadly', 'as', 'GPTs.']

GPT architecture fundamentally takes a stream of tokens as an input, and it returns hidden representation (can be thought of contextual embedding vectors) of the stream of tokens as an output after. If the number of input tokens to the GPT model is $T$ then the number of output context vectors will also be $T$. Since a GPT model can only support a maximum context length of $T_{max}$ tokens, therefore it makes sense to provide $T_{max}$ number of tokens as an input sequence to the GPT model.

Suppose, for this hypothetical example, the GPT model can only support maximum context length of 5 tokens ($T_{max} = 5$). Clearly, you can see that the input tokenized corpus has a stream of tokens that has length of more than $T_{max}$. Therefore, if we want to process this stream of tokens through the GPT model, then we need to sample the token stream via a concept called sliding window.

This sliding window technique involves moving a window of a fixed size (the maximum number of tokens the model can handle at one time, $T_{max}$) across the long input sequence. The window “slides” over the sequence, typically moving forward by one or more tokens after each step (called stride), to cover different parts of the sequence. Each sliding window segment becomes an input example sequence which is then fed into the model separately.

Stride: 1 token

Corpus sequence: ['Generative', 'pre-trained', 'transformers', '(GPT)', 'are', 'a', 'type', 'of', 'large', 'language', 'model', '(LLM)', 'and', 'a', 'prominent', 'framework', 'for', 'generative', 'artificial', 'intelligence.', 'They', 'are', 'artificial', ...,'as', 'GPTs.']

[------------, -------------, --------------, -------, -----] (window size = max context length = 5 tokens)

[-------------, --------------, -------, -----, ----] (window size = max context length = 5 tokens)

[--------------, -------, -----, ----, -----] (window size = max context length = 5 tokens)

Input Example 1: ['Generative', 'pre-trained', 'transformers', '(GPT)', 'are']

Input Example 2: ['pre-trained', 'transformers', '(GPT)', 'are', 'a']

Input Example 3: ['transformers', '(GPT)', 'are', 'a', 'type']

...

Input Example N: ['referred', 'to', 'broadly', 'as', 'GPTs.']

Note that the above input examples are created by taking a stride of 1 token. The stride means the number of tokens that we slide over the window when we move forward in the token sequence. For example, when we use stride of 2 tokens then the input examples will look like:

Stride: 2 tokens

Corpus sequence: ['Generative', 'pre-trained', 'transformers', '(GPT)', 'are', 'a', 'type', 'of', 'large', 'language', 'model', '(LLM)', 'and', 'a', 'prominent', 'framework', 'for', 'generative', 'artificial', 'intelligence.', 'They', 'are', 'artificial', ...,'as', 'GPTs.']

[------------, -------------, --------------, -------, -----] (window size = max context length = 5 tokens)

[--------------, -------, -----, ----, -----] (window size = max context length = 5 tokens)

[-----, ----, -----, ----, -------] (window size = max context length = 5 tokens)

Input Example 1: ['Generative', 'pre-trained', 'transformers', '(GPT)', 'are']

Input Example 2: ['transformers', '(GPT)', 'are', 'a', 'type']

Input Example 3: ['are', 'a', 'type', 'of', 'large']

...

Input Example N: ['referred', 'to', 'broadly', 'as', 'GPTs.']

Now you may think that which stride is better? Is it stride of 1 token or a stride of 2 tokens? In theory, both are bad! The reason is overfitting. To understand this better, let’s consider the true target tokens at each token position for stride of 1 token examples.

Stride: 1 token

Input Example 1: ['Generative', 'pre-trained', 'transformers', '(GPT)', 'are']

Target Example 1: ['pre-trained', 'transformers', '(GPT)', 'are', 'a']

Input Example 2: ['pre-trained', 'transformers', '(GPT)', 'are', 'a']

Target Example 2: ['transformers', '(GPT)', 'are', 'a', 'type']

Input Example 3: ['transformers', '(GPT)', 'are', 'a', 'type']

Target Example 3: ['(GPT)', 'are', 'a', 'type', 'of']

Loss pairs: (input, target): Number of times it appears

('Generative', 'pre-trained'): 1

('pre-trained', 'transformers'): 2

('transformers', '(GPT)'): 3

('(GPT)', 'are'): 3

('are', 'a'): 3

('a', 'type'): 2

('type', 'of'): 1

Note that the loss from an example input sequence will be the sum of all the losses incurred at individual token positions. If we have a batch of $b$ examples then, the loss for the entire batch will be calculated as:

[ L = \sum_{j = 1}^{b} \sum_{i = 1}^{T_{max}} crossEntropyLoss(\mathbf{t} _{true}^{(i, j)}, \mathbf{t} _{pred}^{(i, j)}) ]

Where $\mathbf{t} _{true}$ and $\mathbf{t} _{pred}$ represent the true and predicted token representation respectively. If we pass these 3 examples to the GPT model, then we are overestimating the cross entropy loss in the batch of examples for some (input, target) tokens. For example, ('are', 'a') appears 3 times in the training batch and the loss for this pair will be calculated 3 times in the batch. Since we perform backpropagation based on the batch loss, the model will be overfitted if the model sees an (input, target) pair multiple times.

When the stride is small, such as 1 token, each subsequent window overlaps heavily with the previous window. This means that much of the data in one input example is repeated in the next. For example, with a stride of 1, the second window will differ from the first by only one token. This high overlap can lead to a situation where the model starts to memorize the specific sequences and their slight variations rather than learning more general patterns which might not be as relevant in general usage or unseen data.

As you might have guessed that the stride of 2 tokens will produce a less overfitted model than the stride of 1 token. Increasing the stride to 2 tokens reduces the overlap between successive windows but still has some degree of redundancy. This setup can help mitigate overfitting compared to a stride of 1 but may still not be sufficient. Therefore, we need the stride of as large as maximum context length ($T_{max}$) where the overlap between successive windows will be literally zero!

Now it is time to create the input and target tokens pair from a continuous stream of tokens so that this can be fed to the GPT model under the supervised learning setup. The strategy that I would use is as follows:

Stride: Tmax tokens (max context length)

Corpus sequence: ['Generative', 'pre-trained', 'transformers', '(GPT)', 'are', 'a', 'type', 'of', 'large', 'language', 'model', '(LLM)', 'and', 'a', 'prominent', 'framework', 'for', 'generative', 'artificial', 'intelligence.', 'They', 'are', 'artificial', ...,'as', 'GPTs.']

[------------, -------------, --------------, -------, -----] (window size = max context length = 5 tokens)

[---, ------, ----, -------, ----------] (window size = max context length = 5 tokens)

[-------, -------, -----, ---, -----------] (window size = max context length = 5 tokens)

Input Example 1: ['Generative', 'pre-trained', 'transformers', '(GPT)', 'are']

Input Example 2: ['a', 'type', 'of', 'large', 'language']

Input Example 3: ['model', '(LLM)', 'and', 'a', 'prominent']

...

Input Example N: ['referred', 'to', 'broadly', 'as', 'GPTs.']

Target Example 1: ['pre-trained', 'transformers', '(GPT)', 'are', 'a']

Target Example 2: ['type', 'of', 'large', 'language', 'model']

Target Example 3: ['(LLM)', 'and', 'a', 'prominent', 'framework']

...

Target Example N: ['to', 'broadly', 'as', 'GPTs.', '<|endoftext|>']

Note that when I am using the stride of $T_{max}$ tokens, there is no redundancy of tokens as the windows are not overlapped. Moreover, the target tokes are always created by shifting the input tokens by 1 position as the sole objective of GPT is to predict the next token in a sequence. This above pair of input and target tokens example becomes the dataset for the GPT model which is needed for supervised training.

3.3. Create Training Dataset

Suppose, I want to train the GPT model on the text extracted from the same Romeo and Juliet book that I mentioned before. To create the supervised dataset for training the GPT model, we first need to tokenize the corpus, and they apply the sliding window sampling. Let’s say the name of the dataset class is RomeoDataset which is a subclass of PyTorch’s Dataset class. You might know that any Dataset class must implement the following two methods: __len__ and __getitem__. The __len__ should return the total number of examples or instances present in the dataset. The __getitem__ should return the $i$-th example or instance from the dataset when called on index $i$. The RomeoDataset should store the text data of the corpus, so it needs the corpus file path, and it should also need a tokenizer to tokenize the corpus. Since it will sample the example by sliding window, therefore, it will also need the maximum supported context length.

import torch, tiktoken

from pathlib import Path

from torch.utils.data import Dataset

from typing import Tuple

class RomeoDataset(Dataset):

def __init__(self,

corpus_file_path: Path,

tokenizer: "tiktoken.tokenizer",

max_context_len: int) -> None:

super(RomeoDataset, self).__init__()

self.tokenizer = tokenizer

self.Tmax = max_context_len

with open(corpus_file_path, "r") as f:

raw_text = f.read()

self.enc_text = self.tokenizer.encode(raw_text,

allowed_special={"<|endoftext|>"})

self.enc_text.append(self.tokenizer.eot_token) # eot token is needed for last example

def __len__(self) -> int:

length = torch.floor(torch.tensor((len(self.enc_text)-1)/self.Tmax)) # excludes eot token

return int(length.item())

def __getitem__(self, index: int) -> Tuple[torch.tensor, torch.tensor]:

start = index * self.Tmax

end = start + self.Tmax

input_x = torch.tensor(self.enc_text[start: end])

target_y = torch.tensor(self.enc_text[start+1: end+1])

return (input_x, target_y)

Note that in the __getitem__ method, I have implemented the sliding window method of data sampling. Moreover, the stride is always set to $T_{max}$ to prevent overfitting. For the last example from the dataset, the target token at the last token position needs to be <|endoftext|> token. For this reason, we have to add an extra <|endoftext|> token at the end of text corpus.

cwd = Path.cwd()

corpus_file_path = Path(cwd, "tokenizer/corpus/pg1513.txt") # Romeo and Juliet Book

tokenizer = tiktoken.get_encoding("gpt2")

dataset = RomeoDataset(corpus_file_path, tokenizer, 5) # Context length is taken as 5 for simplicity

print("Length of the dataset: ", len(dataset)) # calls dataset.__len__()

print("Example 1: ", dataset[0]) # calls dataset.__getitem__(0)

print("Example 2: ", dataset[1]) # calls dataset.__getitem__(1)

print("Example 3: ", dataset[2]) # calls dataset.__getitem__(2)

Length of the dataset: 10066

Example 1: (tensor([ 171, 119, 123, 464, 4935]), tensor([ 119, 123, 464, 4935, 20336]))

Example 2: (tensor([20336, 46566, 286, 43989, 290]), tensor([46566, 286, 43989, 290, 38201]))

Example 3: (tensor([38201, 198, 220, 220, 220]), tensor([198, 220, 220, 220, 220]))

As shown above, the total number of examples will be 10,066 if we set the maximum context length as 5. As expected, the target token IDs are same as input token IDs but shifted by 1 position.

The final step would be to collate the individual examples to form a batch of examples which will be passed to the GPT model for training. At one training step, the GPT model will process all the examples in a batch and updates the parameters of the model exactly once per each batch. This is called a training step of the mini-batch gradient descent algorithm. A training epoch is defined as the iteration of training steps when the model processes the entire training dataset exactly once.

batch_size = 32

dataset_len = 10066

num_of_batches = floor(10066 / 32) = floor(314.56) = 314

Note that the last batch doesn’t have a full batch size, so I am going to drop the last batch to maintain homogeneity. In 1 training epoch, the parameters of the GPT model will be updated 314 times (exactly one update per batch) which means, in 1 training epoch, the model undergoes 314 training steps. If the model is trained with 10 epochs, then the parameters will be updated overall 3,140 times!

To create a batch of examples, I will use PyTorch’s DataLoader class which takes the dataset object and returns a batch on demand.

from torch.utils.data import DataLoader

dataloader = DataLoader(dataset=dataset, batch_size=4, shuffle=True, drop_last=True)

batch = next(iter(dataloader))

print("Number of batches: ", len(dataloader))

print("input_x: \n", batch[0]) # (b, Tmax)

print("target_y: \n", batch[1]) # (b, Tmax)

Number of batches: 2516

input_x:

tensor([[ 543, 523, 1718, 1245, 198],

[ 508, 3892, 4320, 319, 6642],

[ 13, 198, 3109, 9862, 790],

[ 2612, 351, 45365, 27360, 198]])

target_y:

tensor([[ 523, 1718, 1245, 198, 1722],

[ 3892, 4320, 319, 6642, 26],

[ 198, 3109, 9862, 790, 6405],

[ 351, 45365, 27360, 198, 17278]])

Note that the DataLoader returns an object with is an iterator where each item represents a batch (unfortunately, you can’t use [] to use access them using index!). To break the patterns in the data, I am shuffling the examples before sampling from the dataset. This ensures that the data instances or examples are sampled randomly from the dataset, so each batch will see a random collection of examples. Moreover, it also ensures that the shuffling order or sampling order will be different in each training epoch. This dataloader will be the main input for training the GPT which has both the input_x and target_y in the form of batches.

What’s Next?

In next blog, I will cover the Embedding layer, Attention layer and Output layer which are the building blocks of GPT model. I will build the model step by step, entirely from scratch using PyTorch.

Happy learning! 😃

Reference Books

- Sebastian Raschka, Build a Large Language Model (From Scratch)

- Aston Zhang, Dive into Deep Learning

- Daniel Jurafsky, Speech and Language Processing

- Huggingface tokenizers

Written by

Soumen Mondal (Email: 23m2157@iitb.ac.in), MS in AI and DS, CMInDS, IIT Bombay